Ah to Be Young Again and Also a Robot

| R.U.R. | |

|---|---|

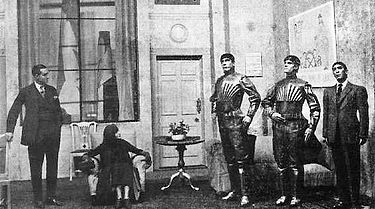

A scene from the play, showing three robots | |

| Written by | Karel Čapek |

| Date premiered | 2 January 1921 |

| Original language | Czech |

| Genre | Scientific discipline fiction |

R.U.R. is a 1920 science-fiction play by the Czech writer Karel Čapek. "R.U.R." stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum's Universal Robots,[1] a phrase that has been used equally a subtitle in English language versions).[2] The play had its world premiere on 2 January 1921 in Hradec Králové;[3] information technology introduced the word "robot" to the English language and to scientific discipline fiction equally a whole.[4] R.U.R. soon became influential after its publication.[five] [6] [seven] By 1923 it had been translated into thirty languages.[5] [eight] R.U.R. was successful in its time in Europe and Due north America.[9] Čapek later took a different approach to the same theme in his 1936 novel War with the Newts, in which non-humans become a servant-course in human society.[x]

Premise [edit]

The play begins in a factory that makes artificial people, called roboti (robots), whom humans take created from synthetic organic matter. (As living creatures of bogus flesh and blood rather than machinery, the play'southward concept of robots diverges from the idea of "robots" as inorganic. After terminology would call them androids.) Robots may exist mistaken for humans and can think for themselves. Initially happy to piece of work for humans, the robots revolt and cause the extinction of the human race.

Characters [edit]

The robots breaking into the factory at the cease of Human action III

Parentheses indicate names which vary co-ordinate to translation. On the meaning of the names, see Ivan Klíma, Karel Čapek: Life and Piece of work, 2002, p. 82.

Homo [edit]

- Harry Domin (Domain): Full general Managing director, R.U.R.

- Fabry: Chief Engineer, R.U.R.

- Dr. Gall: Head of the Physiological Department, R.U.R.

- Dr. Hellman (Hallemeier): Psychologist-in-Primary

- Jacob Berman (Busman): Managing Director, R.U.R.

- Alquist: Clerk of the Works, R.U.R.

- Helena Glory: President of the Humanity League, daughter of President Glory

- Emma (Nana): Helena's maid

Robots and robotesses [edit]

- Marius, a robot

- Sulla, a robotess

- Radius, a robot

- Primus, a robot

- Helena, a robotess

- Daemon (Damon), a robot

Plot [edit]

Human action I [edit]

Helena, the girl of the president of a major industrial ability, arrives at the island mill of Rossum'due south Universal Robots. Hither, she meets Domin, the General Director of R.U.R., who relates to her the history of the company. Rossum had come up to the island in 1920 to study marine biology. In 1932, Rossum had invented a substance similar organic matter, though with a different chemical composition. He argued with his nephew about their motivations for creating artificial life. While the elder wanted to create animals to evidence or disprove the existence of God, his nephew only wanted to get rich. Immature Rossum finally locked away his uncle in a lab to play with the monstrosities he had created and created thousands of robots. By the fourth dimension the play takes place (circa the twelvemonth 2000),[xi] robots are inexpensive and available all over the world. They have become essential for manufacture.

Afterward meeting the heads of R.U.R., Helena reveals that she is a representative of the League of Humanity, an organization that wishes to liberate the robots. The managers of the manufacturing plant find this absurd. They see robots as appliances. Helena asks that the robots exist paid, but according to R.U.R. management, the robots do non "like" anything.

Eventually Helena is convinced that the League of Humanity is a waste of money, but nevertheless argues robots have a "soul". Later, Domin confesses that he loves Helena and forces her into an appointment.

Deed II [edit]

Ten years have passed. Helena and her nurse Nana discuss current events, the decline in homo births in particular. Helena and Domin reminisce about the day they met and summarize the last ten years of globe history, which has been shaped by the new worldwide robot-based economy. Helena meets Dr. Gall's new experiment, Radius. Dr. Gall describes his experimental robotess, likewise named Helena. Both are more than advanced, fully-featured robots. In underground, Helena burns the formula required to create robots. The revolt of the robots reaches Rossum's isle as the human activity ends.

Human action Three [edit]

The characters sense that the very universality of the robots presents a danger. Echoing the story of the Belfry of Boom-boom, the characters talk over whether creating national robots who were unable to communicate across their languages would accept been a expert idea. Equally robot forces lay siege to the manufacturing plant, Helena reveals she has burned the formula necessary to make new robots. The characters complaining the terminate of humanity and defend their actions, despite the fact that their imminent deaths are a direct result of their choices. Busman is killed while attempting to negotiate a peace with the robots. The robots storm the factory and kill all the humans except for Alquist, the company'south principal engineer. The robots spare him because they recognize that "he works with his hands like the robots."[12]

Epilogue [edit]

Years take passed. Alquist, who still lives, attempts to recreate the formula that Helena destroyed. He is a mechanical engineer, though, with insufficient knowledge of biochemistry, and so he has made footling progress. The robot government has searched for surviving humans to help Alquist and institute none live. Officials from the robot government beg him to consummate the formula, even if information technology ways he will have to kill and dissect other robots for it. Alquist yields. He volition kill and dissect robots, thus completing the circle of violence begun in Act Two. Alquist is disgusted. Robot Primus and Helena develop human feelings and autumn in dear. Playing a hunch, Alquist threatens to dissect Primus and so Helena; each begs him to take him- or herself and spare the other. Alquist now realizes that Primus and Helena are the new Adam and Eve, and gives charge of the world to them.

Čapek'south conception of robots [edit]

U.S. WPA Federal Theatre Projection poster for the production past the Marionette Theatre, New York, 1939

The robots described in Čapek's play are non robots in the popularly understood sense of an automaton. They are not mechanical devices, simply rather artificial biological organisms that may be mistaken for humans. A comic scene at the get-go of the play shows Helena arguing with her future hubby, Harry Domin, considering she cannot believe his secretary is a robotess:

DOMIN: Sulla, let Miss Glory accept a look at y'all.

HELENA: (stands and offers her hand) Pleased to meet you. Information technology must be very hard for y'all out here, cut off from the rest of the world.

SULLA: I exercise not know the rest of the world Miss Glory. Please sit downward.

HELENA: (sits) Where are you from?

SULLA: From hither, the manufactory.

HELENA: Oh, you were built-in here.

SULLA: Yep I was made hither.

HELENA: (startled) What?

DOMIN: (laughing) Sulla isn't a person, Miss Glory, she's a robot.

HELENA: Oh, please forgive me...

His robots resemble more than modern conceptions of man-made life forms, such as the Replicants in Bract Runner, the "hosts" in the Westworld Television set serial and the humanoid Cylons in the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica, but in Čapek's time there was no conception of modern genetic engineering (DNA's function in heredity was not confirmed until 1952). At that place are descriptions of kneading-troughs for robot peel, dandy vats for liver and brains, and a manufactory for producing bones. Nerve fibers, arteries, and intestines are spun on manufactory bobbins, while the robots themselves are assembled like automobiles.[xiii] Čapek's robots are living biological beings, but they are notwithstanding assembled, as opposed to grown or born.

I critic has described Čapek's robots as epitomizing "the traumatic transformation of mod gild by the First Globe War and the Fordist assembly line."[13]

Origin of the word "robot" [edit]

The play introduced the word robot, which displaced older words such equally "automaton" or "android" in languages around the world. In an article in Lidové noviny, Karel Čapek named his brother Josef equally the true inventor of the word.[14] [15] In Czech, robota means forced labour of the kind that serfs had to perform on their masters' lands and is derived from rab, meaning "slave".[xvi]

The proper noun Rossum is an allusion to the Czech word rozum, significant "reason", "wisdom", "intellect" or "common sense".[x] Information technology has been suggested that the allusion might be preserved past translating "Rossum" as "Reason" simply simply the Majer/Porter version translates the word every bit "Reason".[17]

Product history [edit]

Cover of the offset edition of the play designed past Josef Čapek, Aventinum, Prague, 1920

The work was published in Prague by Aventinum in 1920, after being postponed, and, premiered at the city's National Theatre on 25 January 1921, although an amateur group had by then already presented a production.[notes 1]

R.U.R. was translated from Czech into English by Paul Selver and adapted for the stage in English by Nigel Playfair in 1923. Selver'southward translation abridged the play and eliminated a character, a robot named "Damon".[18] In April 1923 Basil Dean produced R.U.R. for the Reandean Visitor at St Martin's Theatre, London.[19]

The American première was at the Garrick Theatre in New York Urban center in Oct 1922, where it ran for 184 performances, a production in which Spencer Tracy and Pat O'Brien played robots in their Broadway debuts.[20]

Information technology also played in Chicago and Los Angeles during 1923.[21] In the late 1930s, the play was staged in the U.S. past the Federal Theatre Project's Marionette Theatre in New York.

In 1989, a new, entire translation past Claudia Novack-Jones restored the elements of the play eliminated by Selver.[18] [22] Another unabridged translation was produced by Peter Majer and Cathy Porter for Methuen Drama in 1999.[17]

Disquisitional reception [edit]

Reviewing the New York production of R.U.R., The Forum magazine described the play as "thought-provoking" and "a highly original thriller".[23] John Clute has lauded R.U.R. as "a play of exorbitant wit and about demonic energy" and lists the play every bit i of the "classic titles" of inter-war science fiction.[24] Luciano Floridi has described the play thus: "Philosophically rich and controversial, R.U.R. was unanimously acknowledged equally a masterpiece from its start advent, and has become a classic of technologically dystopian literature."[25] Jarka M. Burien called R.U.R. a "theatrically effective, prototypal sci-fi melodrama".[9]

On the other hand, Isaac Asimov, writer of the Robot series of books and creator of the Three Laws of Robotics, stated: "Capek's play is, in my own opinion, a terribly bad i, merely it is immortal for that one give-and-take. It contributed the give-and-take 'robot' non only to English simply, through English language, to all the languages in which science fiction is at present written."[iv] In fact, Asimov's "Laws of Robotics" are specifically and explicitly designed to prevent the kind of situation depicted in R.U.R. – since Asimov's Robots are created with a built-in total inhibition confronting harming human beings or disobeying them.

Adaptations [edit]

- On 11 February 1938, a 35-minute adaptation of a section of the play was broadcast on BBC Telly—the first piece of goggle box science-fiction always to be broadcast. Some low quality stills have survived, although no recordings of the product are known to exist.[26]

- In 1941, BBC radio presented a radio play version,[27] and in 1948, another telly adaptation—this time of the entire play, running to xc minutes—was screened by the BBC. In this version, Radius was played by Patrick Troughton who was after the second actor to play The Physician in Doctor Who. [28] None of these iii productions survives in the BBC'southward athenaeum. BBC Radio 3 dramatised the play again in 1989, and this version has been released commercially.[29]

- The Hollywood Theater of the Ear dramatized an unabridged sound version of R.U.R. which is available on the drove 200010: Tales of the Next Millennia. [30] [31]

- In August 2010, Portuguese multi-media artist Leonel Moura'south R.U.R.: The Birth of the Robot, inspired by the Čapek play, was performed at Itaú Cultural in São Paulo, Brazil. It utilized actual robots on stage interacting with the human actors.[32]

- An electro-rock musical, Salvage The Robots is based on R.U.R., featuring the music of the New York Urban center pop-punk art-stone band Hagatha.[33] This version with book and adaptation past E. Ether, music by Rob Susman, and lyrics by Clark Render was an official option of the 2014 New York Musical Theatre Festival season.[34]

- On 26 November 2015 The RUR-Play: Prologue, the world's first version of R.U.R. with robots actualization in all the roles, was presented during the robot operation festival of Cafe Neu Romance at the gallery of the National Library of Technology in Prague.[35] [36] [37] The concept and initiative for the play came from Christian Gjørret, leader of "Vive Les Robots!" [38] who, on 29 January 2012, during a coming together with Steven Canvin of LEGO Group, presented the proposal to Lego, that supported the piece with the LEGO MINDSTORMS robotic kit. The robots were built and programmed past students from the R.U.R squad from Gymnázium Jeseník. The play was directed by Filip Worm and the squad was led by Roman Chasák, both teachers from the Gymnázium Jeseník.[39] [40]

In popular civilization [edit]

- Eric, a robot constructed in Britain in 1928 for public appearances, diameter the letters "R.U.R." beyond its chest.[41]

- The 1935 Soviet movie Loss of Sensation, though based on the 1929 novel Iron Riot, has a similar concept to R.U.R., and all the robots in the picture show prominently display the proper noun "R.U.R."[42]

- In the American science fiction television series Dollhouse, the adversary corporation, Rossum Corp., is named later the play.[43]

- In the Star Trek episode "Requiem for Methuselah", the android'southward name is Rayna Kapec (an anagram, though not a homophone, of Capek, Čapek without its háček).[44]

- In the two-function Batman: The Animated Series episode "Eye of Steel", the scientist that created the HARDAC car is named Karl Rossum. HARDAC created mechanical replicants to replace existing humans, with the ultimate goal of replacing all humans. One of the robots is seen driving a auto with "RUR" as the license plate number.[45]

- In the 1977 Md Who serial "The Robots of Death", the robot servants turn on their human masters nether the influence of an individual named Taren Capel.[46]

- In the 1995 science fiction series The Outer Limits, in the remake of the "I, Robot" episode from the original 1964 series, the business organisation where the robot Adam Link is built is named "Rossum Hall Robotics".[ citation needed ]

- The 1999 Blake's 7 radio play The Syndeton Experiment included a character named Dr. Rossum who turned humans into robots.[47]

- In the "Fear of a Bot Planet" episode of the animated science fiction TV series Futurama, the Planet Express crew is ordered to brand a delivery on a planet called "Chapek 9", which is inhabited solely by robots.[48]

- In Howard Chaykin's Fourth dimension² graphic novels, Rossum'due south Universal Robots is a powerful corporation and maker of robots.[49]

- In Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone, when Wolff wakes Chalmers, she has been reading a re-create of R.U.R. in her bed. This presages the fact that she is later revealed to exist a gynoid.[ citation needed ]

- In the 2016 video game Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, R.U.R. is performed in an hole-and-corner theater in a dystopian Prague by an "augmented" (cyborg) woman who believes herself to exist the robot Helena.[50]

- In the 2018 British alternative history drama Agatha and the Truth of Murder, Agatha is seen reading R.U.R. to her daughter Rosalind as a bedtime story.

- In the 2021 movie Mother/Android, the play R.U.R. of Karel_Čapek comes up. In the movie, Arthur, an AI programmer , who survived because he knows how they think: Roboti are artificial creatures with living flesh and os components, such as the modern Android is, they look like us, they talk like us. It is a common mistake to take a mod roboti every bit a human. At first, they seem happy to serve men. In the end, a roboti rebellion leads to the extinction of man life. This play introduced the discussion Robot into the human language. It ends with our extinction. Nosotros knew it the moment nosotros gave it a name.

See also [edit]

- AI takeover

- The Steam Human of the Prairies (1868), an early American depiction of a "mechanical homo"

- Tik-Tok, 50. Frank Baum'southward before depiction (1907) of a like entity

- Detroit: Go Human (2018), a narrative video game congenital around a rebellion by androids who become sentient.

References [edit]

Informational notes

- ^ The world premiere was planned to be in the National Theater in Prague, simply had to be postponed to 25 Jan 1921. The amateur theater group Klicpera in Hradec Králové, which was supposed to mount a production afterwards the premiere, as not informed most the date change in the National Theater, so their opening night on 2 January 1921 was the actual world premiere. See: Databáze amatérského divadla, soubor Klicpera

Citations

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2006). The History of Science Fiction . New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 168. ISBN978-0-333-97022-v.

- ^ Kussi, Peter. Toward the Radical Centre: A Čapek Reader. (33).

- ^ Kubařová, Petra (3 Feb 2021) "Světová premiéra R.U.R. byla před 100 lety v Hradci Králové" ("The world premiere of RUR was 100 years ago in Hradec Králové") University of Hradci Králové

- ^ a b Asimov, Isaac (September 1979). "The Vocabulary of Science Fiction". Asimov'south Science Fiction.

- ^ a b Voyen Koreis. "Capek'due south RUR". Archived from the original on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Madigan, Tim (July–August 2012). "RUR or RU Own't A Person?". Philosophy Now. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Rubin, Charles T. (2011). "Car Morality and Human Responsibleness". The New Atlantis. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Ottoman Turkish Translation of R.U.R. – Library Details" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 3 Feb 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ a b Burien, Jarka K. (2007) "Čapek, Karel" in Gabrielle H. Cody, Evert Sprinchorn (eds.) The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama, Book 1. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 224–225. ISBN 0231144229

- ^ a b Roberts, Adam "Introduction", to RUR & War with the Newts. London, Gollancz, 2011, ISBN 0575099453 (pp. vi–ix).

- ^ According to the poster for the play's opening in 1921; see Klima, Ivan (2004) "Introduction" to R.U.R., Penguin Classics

- ^ Čapek, Karel (2001). R.U.R. . translated by Paul Selver and Nigel Playfair. Dover Publications. p. 49.

- ^ a b Rieder, John "Karl Čapek" in Mark Bould (ed.) (2010) Fifty Cardinal Figures in Science Fiction. London, Routledge. ISBN 9780415439503. pp. 47–51.

- ^ "Who did actually invent the give-and-take 'robot' and what does it hateful?". Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Margolius, Ivan (Fall 2017) "The Robot of Prague" Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Friends of Czech Heritage Newsletter no. 17, pp.3-6

- ^ "robot". Free Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on six July 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ a b Klíma, Ivan, Karel Čapek: Life and Piece of work. Catbird Printing, 2002 ISBN 0945774532 (p. 260).

- ^ a b Abrash, Merritt (1991). "R.U.R. Restored and Reconsidered". Extrapolation. 32 (ii): 185–192. doi:10.3828/extr.1991.32.2.184.

- ^ Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (20 May 2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Primal Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN9027234558. Archived from the original on xiii March 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Corbin, John (x Oct 1922). "A Czecho-Slovak Frankenstein". New York Times. p. 16/i. ; R.U.R (1922 production) at the Net Broadway Database

"Spencer Tracy Biography". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

Swindell, Larry. Spencer Tracy: A Biography. New American Library. pp. forty–42. - ^ Butler, Sheppard (16 April 1923). "R.U.R.: A Satiric Nightmare". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 21. ; "Rehearsals in Progress for 'R.U.R.' Opening". Los Angeles Times. 24 November 1923. p. I13.

- ^ Kussi, Peter, ed. (1990). Toward the Radical Center: A Karel Čapek Reader. Highland Park, New Jersey: Catbird Press. pp. 34–109. ISBN0-945774-06-0.

- ^ Holt, Roland (Nov 1922) "Plays Tender and Tough". pp. 970–976. The Forum

- ^ Clute, John (1995). Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 119, 214. ISBN0-7513-0202-three.

- ^ Floridi, Luciano (2002) Philosophy and Computing: An Introduction. Taylor & Francis. p.207. ISBN 0203015312

- ^ Telotte, J. P. (2008). The essential science fiction tv reader. Academy Printing of Kentucky. p. 210. ISBN978-0-8131-2492-6. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ "R.u.r." Radio Times. No. 938. xix September 1941. p. seven. ISSN 0033-8060. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved ix Feb 2018.

- ^ "R.U.R. (Rossum'due south Universal Robots)". Radio Times. No. 1272. 27 February 1948. p. 27. ISSN 0033-8060. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "R.U.R.(Rossum'southward Universal Robots)". Net Archive . Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "2000x: Tales of the Next Millennia". Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ 2000X: Tales of the Next Millennia. ISBN1-57453-530-seven.

- ^ "Itaú Cultural: Emoção Art.ficial "2010 Schedule"". Retrieved half-dozen August 2013.

- ^ "Salvage The Robots the Musical Summary". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Save The Robots: NYMF Developmental Reading Series 2014". Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Buffet Neu Romance – CNR 2015: Live: Vive Les Robots (DNK): The RUR-Play: Prologue". cafe-neu-romance.com. Archived from the original on three Apr 2016. Retrieved xx May 2020.

- ^ "VIDEO: Poprvé bez lidí. Roboti zcela ovládli Čapkovu hru R.U.R." iDNES.cz. 27 November 2015. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "Entertainment Czech republic Robots | AP Annal". www.aparchive.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "Christian Gjørret on robot & performance festival Café Neu Romance". 4 December 2015.

- ^ "VIDEO: Poprvé bez lidí. Roboti zcela ovládli Čapkovu hru R.U.R." iDNES.cz. 27 November 2015.

- ^ "Gymnázium Jeseník si zapsalo jedinečné světové prvenství v historii robotiky i umění". jestyd.cz.

- ^ Wright, Volition; Kaplan, Steven (1994). The Image of Engineering in Literature, the Media, and Society: Selected Papers from the 1994 Conference [of The] Guild for the Interdisciplinary Study of Social Imagery. The Club. p. 3. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017.

- ^ Christopher, David (31 May 2016). "Stalin's "Loss of Sensation": Subversive Impulses in Soviet Science-Fiction of the Not bad Terror". MOSF Periodical of Scientific discipline Fiction. 1 (two). ISSN 2474-0837. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016.

- ^ Dollhouse:"Getting Closer" between 41:52 and 42:45

- ^ Okuda, Michael; Okuda, Denise; Mirek, Debbie (17 May 2011). The Star Trek Encyclopedia. Simon and Schuster. pp. 883–. ISBN978-1-4516-4688-seven. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Stein, Michael (20 February 2012). "Batman and Robin swoop into Prague". Česká pozice. Reuters. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1995). "90 'The Robots of Expiry'". Medico Who: The Discontinuity Guide. London: Dr. Who Books. p. 205. ISBN0-426-20442-v. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017.

- ^ "THE SYNDETON EXPERIMENT". world wide web.hermit.org. Archived from the original on v July 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Booker, Thousand. Keith. Drawn to Tv set: Prime-Time Animation from The Flintstones to Family Guy. pp. 115–124.

- ^ Costello, Brannon (11 October 2017). Neon Visions: The Comics of Howard Chaykin. LSU Press. p. 113. ISBN978-0-8071-6806-6 . Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Deus Ex: Mankind Divided – Strategy Guide. Gamer Guides. thirty September 2016. p. 44. ISBN978-one-63041-378-i . Retrieved 10 February 2018.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to R.U.R.. |

- R.U.R. at Standard Ebooks

- R.U.R. (Rossum'southward Universal Robots) at Project Gutenberg

- R.U.R. in Czech from Projection Gutenberg

- Audio extracts from the SCI-FI-LONDON accommodation

- Karel Čapek bio.

- Online facsimile version of the 1920 kickoff edition in Czech.

- R.U.R. at the Internet Broadway Database

- (in English)

R.U.R. public domain audiobook at LibriVox

R.U.R. public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R.U.R.

0 Response to "Ah to Be Young Again and Also a Robot"

Post a Comment